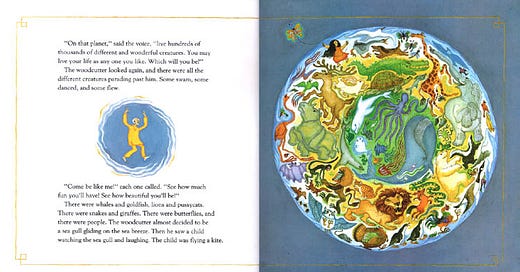

In the children’s book The Mountains of Tibet by Mordecai Gerstein a child is born in the Himalayas, grows up, ages, and dies, whereupon he journeys through the bardo realm where he discovers he could be reborn anywhere as anything. Where does he choose to reincarnate? Amid the mountains he loves, into a very similar life than the simple one he has just finished living albeit this time as a little girl.

For so many of us to imagine re-living the very life we have just lived seems purgatorial and punishing. I have met so many people who fear the idea of reincarnation and being reborn into this decimated culture, this ravaged landscape, this species so intent on violence and destruction. Get me outta here is, fundamentally, the allure of much modern-day Buddhism, overlooking that the initiator of enlightenment and nirvana was himself terrified of rebirth as an ordinary householder with a wife and child and the attendant responsibilities. Surely the little boy in the children’s book has a deeper understanding of love.

Because when we love who we are with and where we are with we know that there is never ever enough time for love. We belong where we are. We become where we are only through the intimacy of lifetimes. Oh to be an owl in the Catskills, a bear, a trillium deep in the forest, a columbine on a cliff, a mother rattler stretched across stones on a mountaintop, a rivulet of water flowing down that mountain, a stone within that mountain, a hawk overhead, a leaf on an oak fluttering down to the ground in the autum to become the soil out of which I will one day grow.

Our pre-civilized ancestors, I believe, experienced this eternal process of both becoming and belonging where our undying love of the land and each other always guided us home. Our grandmother passed and one day her descendants recognized the salmon or the deer or the turkey they were eating as their grandmother returned. They knew how to recognize the subtle signs of timing, naming and place that show us who we have been to each other and who we are now. They knew how to recognize, too, the grandmother returned as an infant, the elder become a child. Who is the elder in such a world? Who matters more or is more special? We are all bound to each other in generous merciful cycles of transformation and becoming. We always know where we are. We always know where we belong. Right here where we’ve always been.

But so many civilized peoples have no sense of where they belong. We are born in one place, may move many times, assess our success by our ability to transcend our origins, strike out on our own, assert our independence. We go on vacation here and there to amuse and distract ourselves but we have forgotten how to be soul pilgrims walking the land in search of who we are and who we have been. Few of us were “recognized” as children, welcomed back into the clan as elders returned, our gifts accrued for lifetimes acknowledged, helped to become who we have always been. We do not know where our souls belong.

I have often been confounded by some people’s intense devotion to their Alma Mater, a “nourishing mother” meant to seperate them from their biological mothers and their sense of place. They give up the intimacy of ecological kith and personal kin to be sorted into a house or college. At the very moment when we might be claiming our long story through initiation and ritual we subsume it to our university or profession. Where did you go to college? What do you do? As if any of this told us who a soul really was. Once we know all souls—human, animal, plant, and fungal—were children of the Magna Mater, the Great Mother who is the true womb of life on this planet and holds the wisdom of who we have been and who we might be.

What it would be like to live a life we want to be reborn to? Surely nothing is more sustainable that that. We are not imagining a bunker in some far-off island where we will retreat during the apocalypse or how to colonizie another planet or even how we might blast off to heaven or nirvana. Instead we look at where we are and ask, “What do I have to do to love where I am, and who I am with, and love coming back HERE. Right here.”

This gives me great joy when I plant trees. In this life I will not see the return of the old growth forests to the Catskills but I can lifetime to lifetime protect this land, nurture this land in a thousand different lives.

If we really knew we were all coming back, every aspect of our lives would change. There would be always be enough time to plant seeds, change directions, and mend a fence. But it would also be urgent that we do so. We are comning back to the world we have made. What world are we making?

How do we fall in love with the world again? How do we know where our bones belong?

Perdita Finn is the author of Take Back the Magic: Conversations with the Unseen World and the forthcoming Mother Magic: Recovering the Love at the Heart of the World. With her husband Clark Strand she is the founder of The Way of the Rose and the co-author of the book of the same name.

She teaches popular workshops on collaborating with the other side. She’ll be teaching online with the Shift Network this summer (Holy Helpers: How an Ancestral Team Can Transform Our Lives), in person (at last!) at Omega in August (Ancestral Magic) and at Kripalu in November (Mother Magic.) She’ll be offering a full slate of online workshops in 2026.

I remember that book!!!! I loved it when I was a kid. I loved revisiting it in the context of your piece. Happy mother's day! ❤️

This is beautiful and profound.