Sons of Liberty, Founding Fathers, Daughters of the American Revolution, and All the Lost Mothers

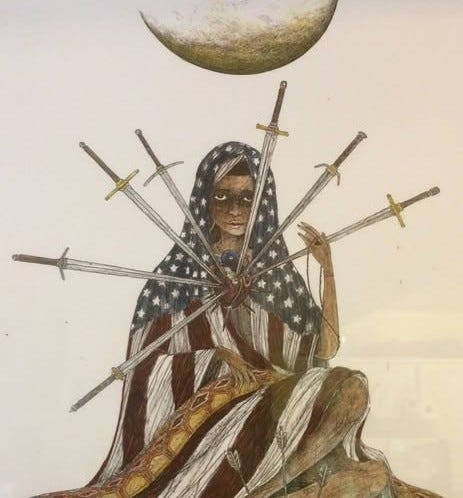

[art: Our Lady of Sorrows by Will Lytle aka Thorneater Comics]

I have an ancestress who come to this land when she was 16, by herself, without any family, in 1640. I did not know her name until I did a deep dive into old records—even though she was the mother of 13 children, each of whom lived, each of whom who would go on to populate this country with their progeny. The name of this young woman who came from Protestant England to Boston, that city on the hill of the Puritans was not Anne or Elizabeth, not Faith or Humility but, remarkably, Dionyse. As in Dionysus, the god of wine and liberation, the freer of slaves, the host of the bacchanal, inviting women back into the forest and their forgotten wildness.

She didn’t stay in Boston but left soon after to join Roger Williams down in the marshlands of what would become Rhode Island. Williams had a different vision than the Pilgrim fathers, instead of wanting to impose a Calvinist vision, he advocated for religious freedom and fair dealing with the indigenous peoples. The Quakers would find refuge in Rhode Island, the first synogogue would be built there, and no one would be required to go to meeting. There would be no witch trials and no witch hangings in Rhode Island either—unlike in all of the surrounding colonies.

The famous Salem witch trials often obscure how ubiquitous such accusations and group executions were in the “new” world that brought all of its violency, misogyny, and patriarchal dominance from the old. Alyce Young, who nursed her own child through the flu when the local preacher’s died, was the first woman formally hung in the new world as a witch—but there would be many others, scores if not hundreds of others, their names recorded only in the faded ledgers of local historical societies, and never actively collected by anyone and remembered. Dionyse would have been in this country for only seven years when Alyce was murdered in Connecticut, only a day’s ride from her home.

Dionyse grew up in Yorkshire, a day’s walk from Pendle Hill, where just before she was born eight women and two male supporters were tried and executed as witches. I cannot help but imagine this young women wanting to escape a world where righteous men convinced of their moral superiority could enact such violence upon women who dared to question their power. Is that why she got on that boat by herself? What was she fleeing—the threat of male violence or the experience of it? What was it like to find herself in Boston—where the good scholars of Harvard were already asserting their right to commit atrocities in the name of religious righteousness? She fled again and found a man who agreed with her that they would join no church, no organization, no meeting house, no religious group. Her grave is impossible to find for this reason because she was buried, when she finally died at a very old age, outside of any formal affiliation. I have often wondered how she took the news of Alyce Young’s hanging. What do you say to your daughters about the world they will grow up in? I ran to the wilderness, you tell them, but civilization was already waiting for me.

Like my ancestress I am wary of any affiliations with civilization—religious or ideological. Today is the “birth” day of our “nation” which is always presented emerging fully formed from heads of the founding fathers, the great men, the landowners asserting their right to self-governance, an idea of “liberty” independent of responsibility to the people who had lived on this land for eons, to the people enslaved and tortured for generations to build it, to the women forced into subservience to populate it anew. I’ve never been patriotic and fear patriotism in all of its expressions—which are fundamentally founded on violence and exclusion.

When a great nation breaks can the land return? Because it is earth herself who is the mother who has been forgotten, paved over, strip mined, irradiated by agricultural chemicals, polluted, clear cut, and hunted into extinction. Today on the fourth of July I wonder what the souls of the dead are praying for. When George Washington died did he have to confront the horrors he had enacteted upon the indigenous peoples whose land he “surveyed” for domination? Did Thomas Jefferson have to finally come to terms with the horrors he had inflicted upon all the people he believed himself to “own”? Did Benjamin Franklin have to confront the truth that no invention could invent a way out of civilization’s endless lust for murder, war, imprisonment and cruelty?

What do I want for America? What miracle would I call upon these ancestors to bring forth? That is the question. What do we want truly, madly, deeply? Do I even want “America”?

Abstract ideas are so dangerous because they have no body and no heart. I want old growth forests with trees so large that we can remember how to be small again. I want rivers teeming with fish and skies filled with birds. I want human beings to remember how to live in collaboration with our mother’s many other children—the plants, the animals, the fish and the fungi, the insects. I want the the vines to engulf the buildings, the moss to cover the rooftops, the dandelions to deconstruct the expressways. Is this liberty? Is this freedom? I don’t know. Who cares? It is life, and life begets more life. All of our abstract notions of “liberty” and “freedom” have wrought is endless violence against the earth and ourselves—the factories, the brothels, the tenements, the addictions, and always more guns, more prisons, and more bombs.

Was there a moment where Dionyse, fleeing civilization again and again, found herself out on the marshes dreaming under the stars about a world she might have found instead? In a few weeks I will go on pilgrimage to a small spit of land sticking into the Atlantic ocean where she was once recorded as living and where her bones might be buried. I want to ask her guidance not in building a great nation but in regreening a beautiful wild earth where she herself could still be wild.

Tonight I will go out in my yard as I always do on the fourth and watch the fireflies who seem to always peek on this day. There’s a dance of romance and courtship not bombs bursting in mid-air. They are trying to light up the world with love. They fly ecstastically up into the darkness becoming one with the stars, bringing the starlight back to earth in their very bodies. Each year there have been less of them. Miraculously, this year their numbers seem to have rebounded. This is what I want: more fireflies and fewer bombs. More love and no more nations.

In her short story “The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas” the great science fiction writer Ursula K. Le Guin describes a city that is a visionary utopia—egalitarian, cultured, and peaceful. Everyone gets along. Everyone is happy and productive. The arts flourish. Life is beautiful. The laws work and are just. This is civilization, perfected at last. America the beautiful. The only small problem is that in a dungeon deep underground a small child is imprisoned in filth and misery.

To remove that child from suffering would mean the end of the magnificent achievements of Omelas. It’s terrible, but it’s only one child after all.

So most of the citizens simply ignore this harsh reality hidden somewhere beneath their finely paved streets. Others visit the child from time to time and feel better about themselves for having recognized that sometimes sacrifices must be made for the betterment of all. They shake their heads, marveling at their own compassion. Some people, however, can tolerate none of it—neither the degradation of the child nor the illusions of Omelas. They are the ones who walk away from it all.

I am the descendant of a woman who kept walking away. And I, too, will try to walk away when I can. I call upon Dionyse and Dionysus himself, the true liberator, to protect me and guide me on that long journey that I know will take not just years but lifetimes. One day may we all walk away from civilization.

Perdita Finn is the author of Take Back the Magic: Conversations with the Unseen World (2024, Running Press) and the forthcoming The Story of Our Mothers: Embodying the Wisdom of Our Ancestors Before Patriarchy (2026, Running Press) With her husband Clark Strand she is the founder of a community devoted to the earth and the Lady by any name you like to call her, and the co-author of The Way of the Rose: The Radical Path of the Divine Feminine Hidden in the Rosary.

Have you read The Dawn of Everything? What you were saying about our democracy emerging fully formed from our founders' heads reminded me of it. In their research they found that Indigenous North American concepts of governance were a much stronger influence on their ideals than the Greeks and Romans.

Thank you Dionyse for bringing us Sophie and Perdita and the promise of real independence for life and living on mother Earth....