On top of everything else on my “to-do” list, amid making a living and paying the bills and caring for my family and friends and trying to squeeze in a little self-care, I am also now, apparently, responsible for healing my messed-up ancestors.

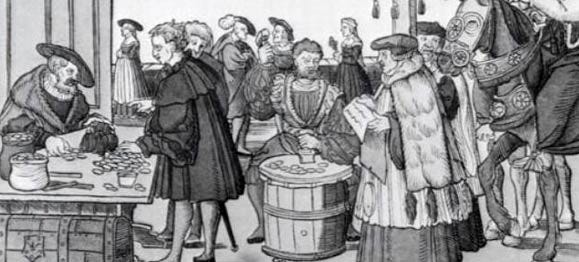

This, by the way, is not a new endeavor but back in vogue again after a long respite since the Reformation. In those days our beloveds on the other side were supposedly languishing in Purgatory and only our prayers (and the money we paid to various priests and other religious authorities for their prayers called “indulgences”) could possibly save them.

Not only had your grandfather been a scoundrel and a creep when he was alive—but now you were stuck forking over the big bucks to the big boys to rescue him when he was dead. No wonder people in an era of reform wanted to give up on the dead altogether. They go to heaven or hell, wipe your hands of them and be done with them. Move along, move along.

Among my ancestors are turncoats, adulterers, hypocrites, misogynists, and maybe even slavers, thieves and murderers. I mean, who knows? I mean, my parents were a mess, and my grandmother was in an out of mental hospitals, and what about that 12th great grandfather kids who moved to what would become Rhode Island with Roger Williams. Don’t tell me that this colonial colonizer with 13 kids was a good guy…

Of course, the whole story of civilization is nothing but a tale of woe. Murder, slavery, incest, torture, abjection, and endless war have been our legacy to our descendants from the moment our species began accumulating stuff and protecting it at all costs. If we trace back any of our ancestors, we will all find ourselves, soon enough, appalled at the horrors our people have inflicted upon each other. Every human being has a genealogy of horrors.

It’s overwhelming to feel the whole heavy weight of ancestral trauma and to also feel responsible for healing that 10,000 years of violence, evil and misery.

It can make you feel like Peter Schoening, the famous mountain climber, who on a terrifying ascent of K2 in the Himalayas, nearly lost five of his fellow climbers when during a storm they all slipped into an almost bottomless crevasse. Schoening, roped to all five, dug his ice axe into a narrow ledge just managing to save himself. The snows swirled, he was losing his grip, his expedition mates dangled above the yawning abyss. With iron-willed determination and superhuman strength, Schoening pulled, strained, and heaved, defying gravity, rescuing them one by one from oblivion.

So many of us feel like this when we approach the dead—that we must rescue them from the abyss of their dysfunction or risk being pulled over into annihilation ourselves. We cannot cut ourselves free—and yet we are impossibly burdened by the extraordinary effort needed to do this lineage healing. We are being dragged down by family histories of abuse of and addiction, violence and depression, sorrow and silence.

The entire endeavor seems to demand heroic effort.

Except we have forgotten that the dead weigh nothing at all—and they have already fallen.

The dead have been released from the tyrannies of patriarchal linear narratives. To die is to remember the entangled intimacies of our souls with one another through the mysteries of deep time. To die is to be healed—of the illusion that we only have one life to get it right, one life to get what we deserve or take what we can. To die is to recover the consolations of eternity where there is always enough time for mercy and justice, reunion and love. What the dead know is that no one is ever let go.

This is why I do not pray for the dead but to them.

I ask the dead to help me, save me, and liberate me from the fantasy that I must make some kind of extra effort to prove that I am worthy of this life. Of this soul. I ask the dead for help with everything—from the most mundane matters of my life to the deepest yearnings of my heart.

The priests of various religions and institutions would like to weigh us down with our responsibilities to the dead—but the dead themselves want to free us from our worries, our isolation, and our fears. When we pray to the dead, and with the dead, we may find ourselves not needing the priests anymore because we have magic and miracles instead.

When we have the dead, we have everything we need and there is nothing that we cannot do.

I pray to the beautiful mother of a friend who died a terminal alcoholic in her own blood and vomit to help me sober up from sugar and claim my life. I pray to my stingy father who cut me out of his will to help me generate miracles with money. I pray, in the midst of the Sixth Extinction by my species of all life on this planet, to the dinosaurs. Help us, I pray to these vanished ancestors, show us how to become small again, teach us how to sing again, and help us to grow wings so that we, too, might one day have no need of ropes and ice axes and remember how to fly.

This has been the free version of my Substack—there is also a paid version ($10 a month) which includes a monthly Zoom conversation with me about the dead. To find out about my upcoming workshops you can go to my website here. To learn more about working with the dead in this way be sure to pre-order my book, Take Back the Magic Conversations with the Unseen World.

I’d also like to give a special shout-out to my beloved soul sister Heatherash Amara who is now on Substack with Out of the Fire which is fabulous. Stay tuned as we prepare a journey together into the long story of our souls.

This, Perdita, feels like the radical heartwood of what you offer. The thing that distinguishes your teaching about the dead from everyone else out there. Instead of a burden, it's a joy. Instead of obligation + duty, it's a chance to be mothered + nourished.

What a fabulously freeing article about the so-called "weight" of our ancestors! I never got it why I needed to heal them, anyway. I agree that I have a long string of miscreants in my lineage as well as interesting and fabulous ancestors. I'm not there yet in asking for help from those who directly hurt me, but I believe I'm getting there.